From the Shadows to the Spotlight

Unveiling the Untold History of Deep Learning

Introduction

Many newcomers to the realm of Deep Learning may find it surprising to come across a blog post detailing the "history" of this field. After all, Deep Learning is often perceived as an emerging, cutting-edge technology, seemingly devoid of any substantial historical background. However, the truth is that Deep Learning can be traced back as far as the 1940s. Its apparent novelty arises from its lack of popularity during certain periods and its numerous name changes. Only recently has it gained widespread recognition under the label of "Deep Learning."

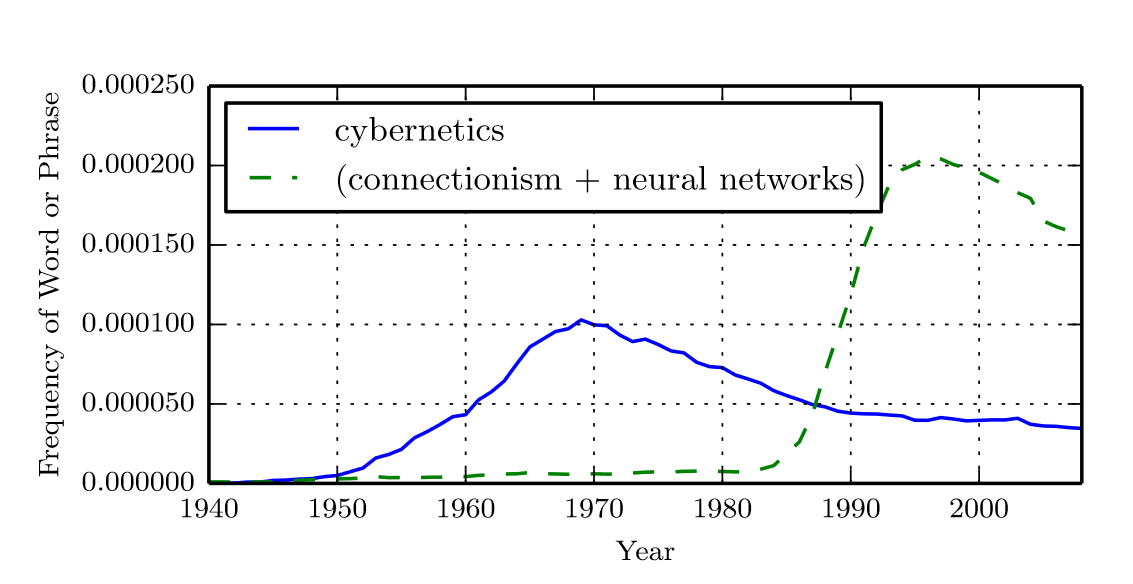

In essence, the history of Deep Learning can be divided into three distinct waves: the cybernetics wave spanning the 1940s to the 1960s, the connectionism wave prevalent during the 1980s and 1990s, and the current resurgence known as deep learning.

Inspiration from the Brain

The early research on Deep Learning drew inspiration from computational models of biological learning, specifically how learning occurs or could potentially occur in the brain. As a result, one of the alternative names used to refer to Deep Learning is artificial neural networks (ANN). A pioneering figure in establishing a correlation between biological neural networks and artificial neural networks was Geoffrey Hinton, often hailed as the "Godfather of AI" due to his significant contributions to the field. Hinton, formerly associated with Google and the University of Toronto, played a crucial role in shaping the understanding and development of Deep Learning.

The neural perspective in Deep Learning is driven by two key ideas. Firstly, the human brain serves as evidence that intelligent behavior is achievable, and reverse engineering the computational principles behind the brain offers a straightforward path to building intelligence. Secondly, exploring the brain and uncovering the underlying principles of human intelligence holds great scientific significance. Thus, machine learning models that provide insights into these fundamental questions offer value beyond their practical engineering applications. In essence, deep learning research can propel our understanding of the human mind, while advancements in deep learning can, in turn, enhance our comprehension of the human brain.

Early Predecessors: Cybernetics

The earliest predecessors of modern deep learning comprised simple linear models inspired by neuroscience. These models aimed to associate a set of n input values denoted as \(x_1, ... ,x_n\), with an output y. The models learned a set of weights \(w_1,...,w_n\) and computed the output as \(f(x,w) = x_1w_1 + ... + x_nw_n\). This initial wave of neural networks was commonly referred to as Cybernetics.

One of the early models mimicking brain functions was the McCullouch-Pitts neuron (1943). It determined whether $f(x,w)$ was positive or negative, classifying inputs into different categories akin to modern binary classifiers. Skilled human operators manually adjusted the weights to minimize the error of the function. Another significant development was the Perceptron, introduced by Rosenblatt in the 1950s. The Perceptron became the first model capable of autonomous weight learning. The Adaptive Linear Element (ADALINE) emerged around the same time, predicting the values of the linear network and learning to do so from input data. This approach still finds application in techniques like Linear Regression. Notably, these models introduced the concept of Stochastic Gradient Descent, a dominant training algorithm that persists today.

Limitations and Backlash

However, these linear models were plagued by limitations. Most notably, they could not learn the XOR function, which can be defined as:

$$\begin{align} f([0,1],w) = 1 \\f([1,0],w) = 1 \\ f([1,1],w) = 0\\ f([0,0],w) = 0 \end{align}$$

The inability of these linear models to learn the XOR function sparked significant criticism and led to a substantial decline in the popularity of biologically inspired learning. Marvin Minsky, a renowned figure in the field, expressed his concerns about perceptron-based models in his book titled "Perceptrons" which garnered considerable attention at the time. You can read more details about this rivalry in the early chapters of the book "Genius Makers"

Shift in Perspective

After this backlash, even though neuroscience is regarded as an important source of inspiration for deep learning researchers, it is no longer the predominant guide for the field. This is because we do not understand the functioning of the brain enough to use it as a guide. But neuroscience has given us hope that a single deep learning algorithm can solve many different tasks. This was found when neuroscientists rewired the brains of ferrets to send visual signals to the auditory processing region instead of the visual cortex. The ferrets could still "see" which proves that there is once single algorithm to solve most of the tasks that the brain encounters. This led to a defragmentation of the machine learning community where researchers from different fields like natural language processing, vision, motion planning, and speech recognition came together and shared their research with each other.

The Connectionism Movement: Second Wave of Neural Network Research

In the 1980s, the field of neural network research experienced a significant resurgence known as the connectionism movement or parallel distributed processing. The core principle behind connectionism is that intelligent behavior can be achieved by connecting many simple computational units together. This concept applies not only to neurons in biological nervous systems but also to hidden units in computational models.

During the connectionism movement, several key concepts emerged that continue to play a central role in today's deep learning. One of these concepts is the distributed representation. Distributed representation aims to reduce the number of neurons required to identify features of the input. For example, identifying a red car, blue bird and green truck would typically require nine neurons and each neuron should learn the concept of colour and object. With distributed representation, each neuron just learns one of the features ( red, green, blue, car, bird, and truck) and thus requires only 6 neurons to learn the same task.

Distributed Representation

One important concept that gained prominence during the connectionism movement is distributed representation. The goal of distributed representation is to reduce the number of neurons required to identify features of the input. Traditionally, identifying different objects with various attributes would require a separate neuron for each combination of attribute and object. However, with distributed representation, each neuron focuses on learning a specific feature, such as color or object type. By employing distributed representation, the number of neurons needed for such tasks can be significantly reduced. For example, instead of using nine neurons to identify a red car, blue bird, and green truck, distributed representation would only require six neurons, each representing one of the features (red, green, blue, car, bird, and truck).

Back-Propagation and LSTM

Another significant accomplishment during the connectionism movement was the successful utilization of back-propagation, a learning algorithm that allows neural networks to adjust their weights based on errors. Backpropagation, first introduced by Rumelhart in 1986 and further developed by LeCun in 1987, became a fundamental technique in training neural networks.

Around the same time, the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) architecture emerged as a crucial advancement. LSTM is widely used in various sequence modeling tasks, including natural language processing, and has been particularly successful in tasks carried out by Google.

Decline in Popularity

The second wave of neural networks driven by connectionism lasted until the mid-1990s. However, as ventures based on neural networks began making unrealistic and ambitious claims while seeking investments, they struggled to deliver on their promises. This disappointment among investors, coupled with the remarkable results achieved by other machine learning techniques like Kernel Machines and Graphical Models, led to a decline in the popularity of neural networks that persisted until 2007.

It is important to acknowledge the rise and fall of neural networks during this period, as it sets the stage for the subsequent resurgence and the current prominence of deep learning in the field of artificial intelligence.

The Third Wave: Rise of Deep Learning

The third wave of neural networks commenced with a groundbreaking breakthrough in 2006, spearheaded by Geoffrey Hinton. Hinton demonstrated that a specific type of neural network known as a deep belief network (DBN) could be effectively trained using a strategy called greedy layer-wise pretraining. This innovation paved the way for significant advancements in the field and marked the beginning of the modern era of deep learning.

During this wave, researchers such as Joshua Bengio, Yann LeCun, and many others made substantial contributions to further refine and enhance deep learning networks. The term "Deep Learning" gained popularity during this period, becoming the common term used to describe these advanced neural network architectures.

One significant aspect that set deep learning apart from other machine learning methods was its superior performance. Networks developed during this time consistently outperformed other AI techniques based on alternative machine learning technologies. Deep learning algorithms demonstrated remarkable capabilities in various domains, including computer vision, natural language processing, speech recognition, and more.

Want to Connect?